The Journey to Make FieldKit Viable

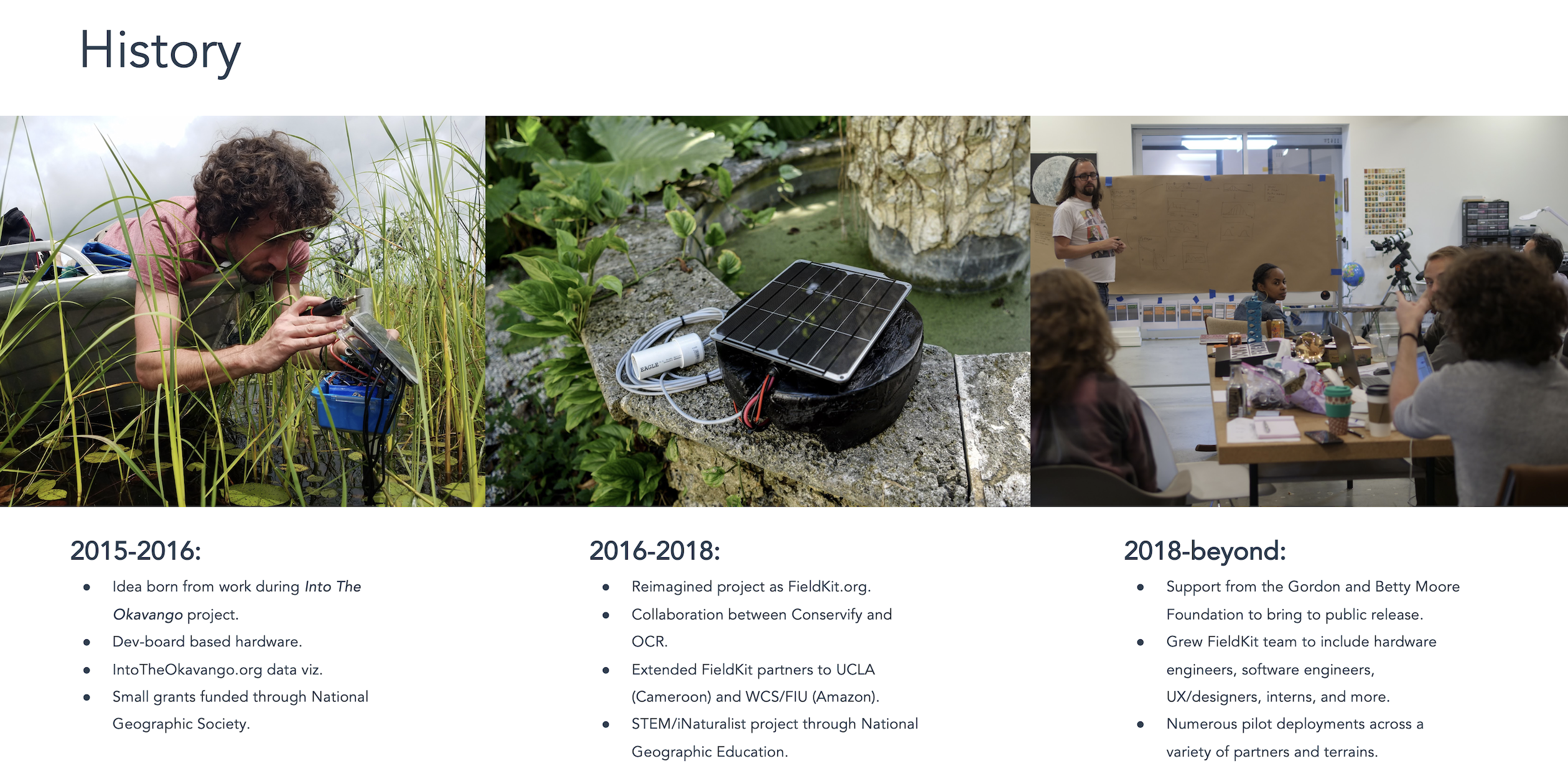

The origin story for FieldKit is similar to the origin story of many projects. A few of us had an idea to do something better than was currently being done so we hacked something together. The first hardware was built on my dining room table, using a combination of Arduinos/Raspberry Pis, development boards, and easily obtainable sensors. The code was quickly taken over by Jacob, on a volunteer basis, to support some of those early tests in Botswana. Jer, and his team in NYC, worked on ways to visualize the data and make sense of it through storytelling. We were all helping a colleague, an ambitious scientist who was interested in trying a new way to do his work.

Over the years the support and funding for FieldKit ebbed and flowed, mostly as a result of the field we work in. Conservation is not a discipline that traditionally accepted the benefits of technology development. Many of the tools that were in use came from repurposed technologies or ecology doctorate projects that spun off into companies. My initial research into conservation technology was part of a small body of work that has spent the better part of a decade trying to change that previous paradigm. It is how my relationship with the National Geographic Society first came to fruition, which ultimately (through folks that I met) resulted in the FieldKit project becoming an idea.

I started Conservify as a mechanism to move that work forward. It is a technology development lab, not unlike others you see in places like Silicon Valley, but we are a nonprofit. All of the work produced at Conservify is completely open source. We also only work in the realm of wildlife conservation and environmental protection. This is important because that means the funding avenues we had for FieldKit are very different than other commercial products that you might see. The lab is funded by philanthropic funding and research grants. That model makes product development very difficult to do, as most of that funding is tied to projects with a defined scope.

We interface with the open science hardware community (specifically GOSH – the Gathering of Open Science Hardware) and the researchers, companies, and nonprofits that frequent those circles. They face many of the same challenges we face in funding and building something sustainable (both financially and environmentally). But the mission behind open science is so fundamentally important, particularly when working with scientists in the global south. Science is underfunded in just about every country in this world, so the work to create better tools is critically important.

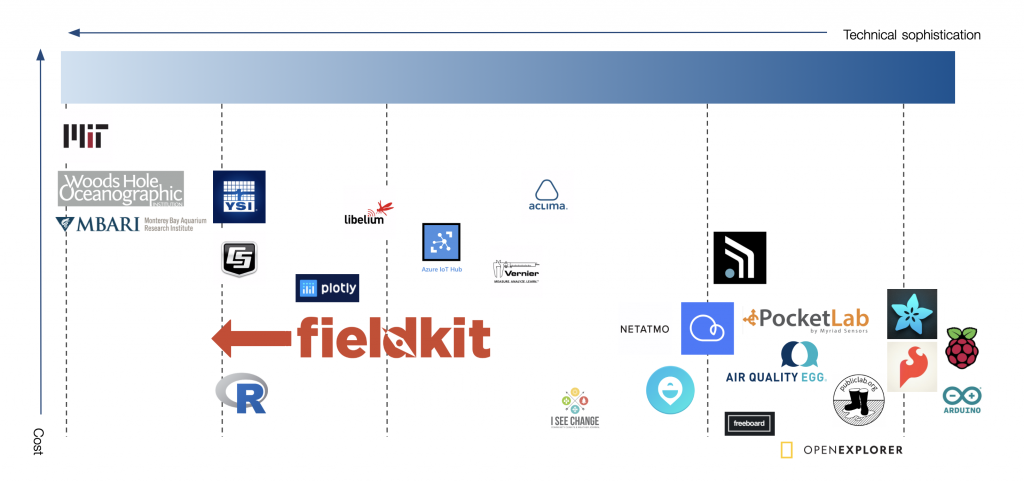

Given that we are a nonprofit, our business model is different than a typical IoT company. We don’t (or more specifically, can’t) charge the same margins on our hardware that commercial entities do. We want people to use FieldKit regardless of whether they are using our hardware or not. Our aim is to engineer lower cost tools and create some easier mechanisms to increase the global capacity at scientifically relevant environmental monitoring. Sometimes that means that we are selling the devices and sometimes that means we are supporting the community in building off our work into something of their own. Given all of these considerations, our team has worked hard to develop FieldKit in the same way that an effective startup would develop their technology. We put the same considerations into user experience, design, and aesthetics that any commercial company would. Just because it is open source and nonprofit does not mean that it has to suck.

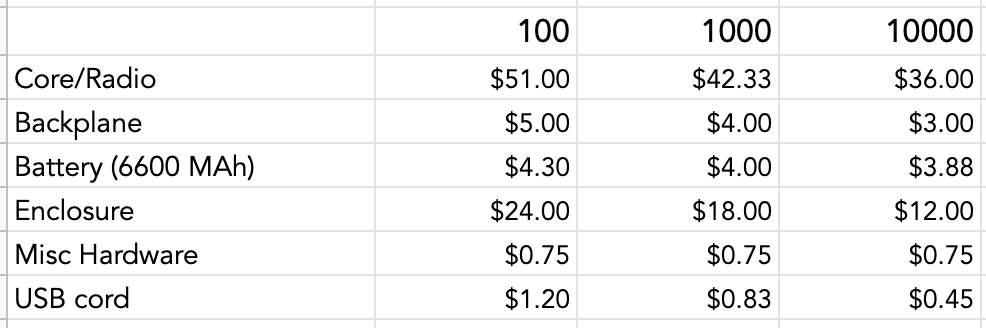

As a result, we have documented our costs pretty well. It is important for us to understand the fundraising ahead, so we can get sufficient grant funding to help and cover it. Above you see a small snapshot of our larger cost analysis, identifying the cost of goods sold for a part of FieldKit. Having “low cost” as a key differentiator means that our users are sensitive to the final unit price, and we must make decisions to optimize that. We also have to be aware that our nonprofit doesn’t have the same purchasing power or funding to buy massive quantities of things. It is a delicate balance for us since much of the traditional grant funding we can get isn’t structured in a way that allows us to pay for that sort of stuff. It also means we have an urgent incentive to get FieldKit operating on revenue as much as possible. Not all of that would be necessarily from selling hardware (we are planning to offer other services – such as custom sensor module design and deployment expedition support) but we are still experimenting with what those will be.

The specific open source licenses that FieldKit will use are also somewhat in flux. Anyone who has developed a product (particularly one that includes hardware, software, and data), knows that this landscape is somewhat convoluted. Despite sitting on the board of OSHWA, I still struggle with wrapping my head around what is best for us. We plan to certify the hardware as open source through the OSHWA certification process but the specific license for that is still being decided. The content of FieldKit.org and our Open Sensor Library (a wiki we haven’t discussed too deeply here) wil be published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License. FieldKit data belongs, first and foremost, to the user. But anything that is pushed to FieldKit.org will be published under a CC0 designation. The software will likely be published under BSD.

But, as I said, we are still evaluating all of this stuff. The plan is to have it decided before the end of the year, well in advance of our public release. If anyone has any comments or ideas about this, I would love to hear them. Please feel free to reach out.