Origin of Species: Darwin

If you’ve ever learned a new skill by doing, you’re familiar with the experience of working your way through a project to completion only to immediately want to start over with all the understanding you’ve gained in the process. Building hardware and deploying it for scientific fieldwork is a very similar crucible. The process of building and assembling tens of remote instrumentation stations will tell you where the unexpected time sinks and pain points are. Deploying them will reveal where the hardware is fragile, inconvenient, or counterintuitive. All the while, you’ll be coming up with features you wish it had.

When I joined the FieldKit project, the general shape of our future hardware was already starting to emerge through this process. Essential as it was, the current hardware couldn’t take the project where it needed to go. A new generation of hardware was going to be required, and since you should never miss an opportunity to give a project a good internal code name which makes you feel like a secret agent, I dubbed this next step in FieldKit evolution ‘Darwin.’

Architecture

Up until Darwin, a Fieldkit station typically consisted of two boards. The “Core” board handled radio communication, GPS, data logging, and power management. The Module handled tending the sensors, whatever they were in a given situation.

So, in an ideal world, what do we want?

- Fewer cables.

- Multiple modules per station (Ideally several different possible configurations, without wasting a lot of space).

- Fewer duplications of expensive and power-hungry microcontrollers.

- Separation of the radios (where our needs are diverse and fast-evolving) from the data logging bits (which are not).

- Easier manufacture and assembly.

- A rudimentary graphical display.

- Standardized module pin-out and footprint.

It might be useful to point out that our goal has never been to hit big venture capital, and have 20,000 units of Fieldkit produced in China for a few bucks apiece, so the pressures that cause many an engineer to condense everything into a single compact board for easy mass production don’t really apply here. That said, starting to break the FieldKit system into separate PCBs does actually improve the manufacturing equation by turning the slowest evolving part of the system into something which can be produced by contract manufacture in larger quantities, without committing us to producing large numbers of those parts of the system which evolve faster. I’ll be writing more on our manufacturing philosophy later.

So, if you work your way through this list assuming that you’re going to end up with several boards and connect them with board-to-board means rather than cables, you end up with an architecture that looks more like this :

Now in an ideal world, Power Management, which is always basically the same, might have ended up on the Upper board, but there were good mechanical engineering reasons not to go that way. (Curse you Meatspace, ruining my fantastic theoretical diagrams!)

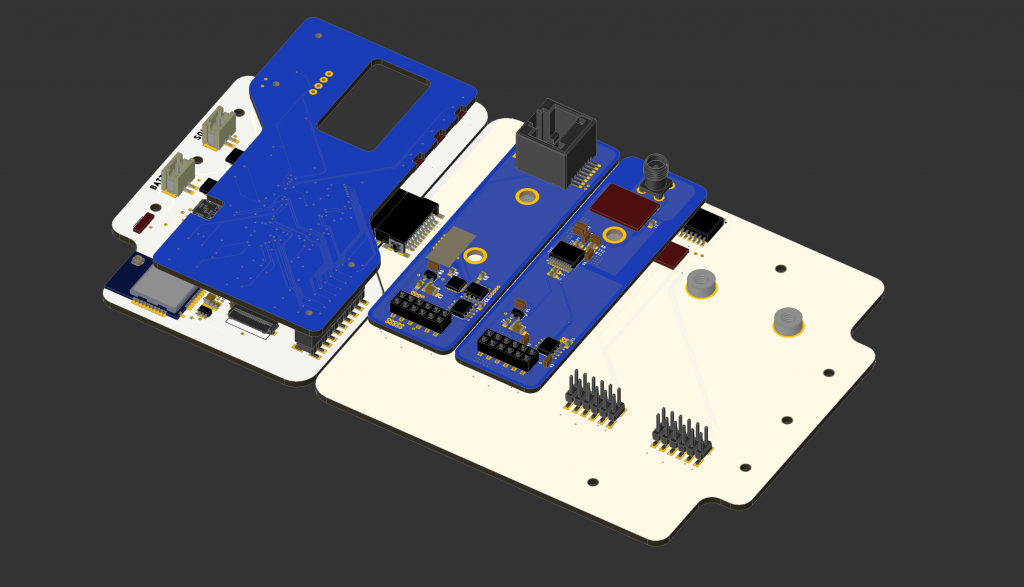

IRL, that ended up looking like this :

There were lots of decisions to be made at each of these boards, so I’m going to write them up individually in a series of posts starting tomorrow.